Nathan Bennett - Managing the social impacts of conservation

This link opens a new window to the full article at NathanBennett.ca.

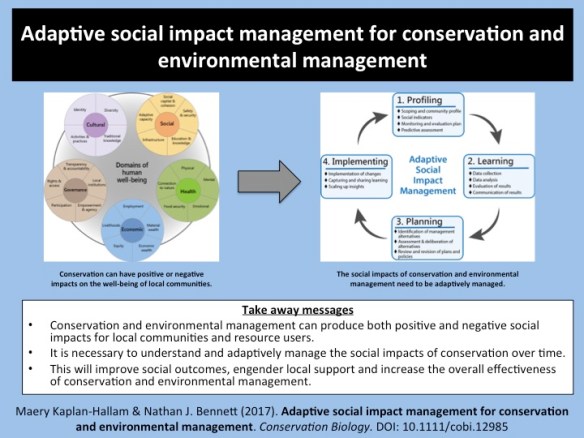

Concerns about the negative consequences of conservation for local people have prompted attention toward how to address the social impacts of different conservation projects, programs, and policies. Inevitably, when actions are taken to protect or manage the environment this will produce a suite of both positive and negative social impacts for local communities and resource users. Thus, a challenge for conservation and environmental decision-makers and managers is maximizing social benefits while minimizing negative burdens across social, economic, cultural, health, and governance spheres of human well-being. The last decade has seen significant advances in both the methods and the metrics for understanding how conservation and environmental management impact human well-being. There has also been increased uptake in socio-economic monitoring programs in conservation organizations and environmental agencies. Yet, little guidance exists on how to integrate the results of social impact monitoring back into conservation management and decision-making. We recommend that conservation organizations and environmental agencies take steps to better understand and address the social impacts of conservation and environmental management. This can be achieved by integrating key components of the adaptive social impact management (ASIM) cycle outlined below, and in a new paper published today in Conservation Biology, into decision-making and management processes**.

“Successful management and conservation of marine ecosystems depends as much on understanding humans as it does on understanding marine organisms and their environment …The social sciences – economics, political science, sociology, anthropology, history, psychology, law, and more – are the formal examination of human society. They study how societies function, how individuals in a society relate to one another, and the institutions societies form. Insights and data from these disciplines in ocean planning are essential to understanding how people use the marine environment, and how they create and may react to new and different forms of ocean governance.”

“Successful management and conservation of marine ecosystems depends as much on understanding humans as it does on understanding marine organisms and their environment …The social sciences – economics, political science, sociology, anthropology, history, psychology, law, and more – are the formal examination of human society. They study how societies function, how individuals in a society relate to one another, and the institutions societies form. Insights and data from these disciplines in ocean planning are essential to understanding how people use the marine environment, and how they create and may react to new and different forms of ocean governance.” Professor Rashid Sumaila is one of the world’s most innovative researchers on the future of the oceans, integrating the social and economic dimensions with ecology, law, fisheries science and traditional knowledge to build novel pathways towards sustainable fisheries. His work has challenged today’s approaches to marine governance and generated exciting new ways of thinking about our relationship to the marine biosphere, such as protecting the high seas as a ‘fish bank’ for the world and using ‘intergeneration discount rates’ for natural resource projects.

Professor Rashid Sumaila is one of the world’s most innovative researchers on the future of the oceans, integrating the social and economic dimensions with ecology, law, fisheries science and traditional knowledge to build novel pathways towards sustainable fisheries. His work has challenged today’s approaches to marine governance and generated exciting new ways of thinking about our relationship to the marine biosphere, such as protecting the high seas as a ‘fish bank’ for the world and using ‘intergeneration discount rates’ for natural resource projects.